Every Pixel a Color

Every Pixel a Color. Dan’s MEGA65 Digest for November 2025.

It’s November, and you know what that means: it’s time to level up our MEGA65 graphics knowledge! In this Digest, we reach another major milestone in our VIC-IV journey: full color character graphics. Type-ins galore, so warm up those coding fingers.

Let’s start with the news, then get right at it.

Dan’s MEGA65 Digest 2025

Dan’s MEGA65 Digest 2025

My talk from Vintage Computer Festival Midwest 2025, Dan’s MEGA65 Digest 2025, is now online. This one looks at the MEGA65 through the lens of this very newsletter over the last few years. It’s a haphazard introduction to the platform, its capabilities, and its community (that’s you!).

I tend to give these talks to audiences that still haven’t heard about us, so there’s always quite a bit of introductory overlap. Hopefully there’s enough new stuff, or at least enthusiastic review, for you to enjoy.

Spring, a limited edition boxed release

Spring, a limited edition boxed release by Gurce’s family.

Gurce’s artistic family is producing a limited edition boxed title for the MEGA65. Entitled Spring, the game is designed by Gurce’s daughter, and will be distributed on floppy disk, with boxes and add-ons by Gurce’s sister.

Spring will be available to the MEGA65 community in strictly limited quantities. If you’d like one, contact Gurce on the Discord. Check out the game’s website for more information, poster art, and a guide to the game.

Featured Files

The Woods of Peril, by Lipi.

The Woods of Peril by Lipi, an original text and graphics adventure game. Music by Gurce. Navigate the forest with cursor keys: rotate left and right, move forward or backward. Follow on-screen prompts in villages and during battle.

Overlord by Drex. Navigate the maze and avoid the Overlord. Listen for his footsteps, avoid his line of sight, and try to make it to the end. Based on Drex’s own Alpha Maze. Use keyboard controls to move: W, A, S, D, and Q and E to rotate.

Yet another core for your home arcade from muse, Mr. Do! is now available. Collect cherries, avoid monsters, and defend yourself by pushing giant apples and throwing your ball.

Recap: Two and four colors per character

In the September Digest, we introduced Super-Extended Attribute Mode (SEAM) and the CHR16 register, a feature that allowed us to commit more memory to graphics to access more features. So far, we only got more screen codes out of the deal, but that’s a pretty big step up! We were able to fill screen memory with ascending screen codes to make a screen-wide bitmap quilt of monochromatic tiles.

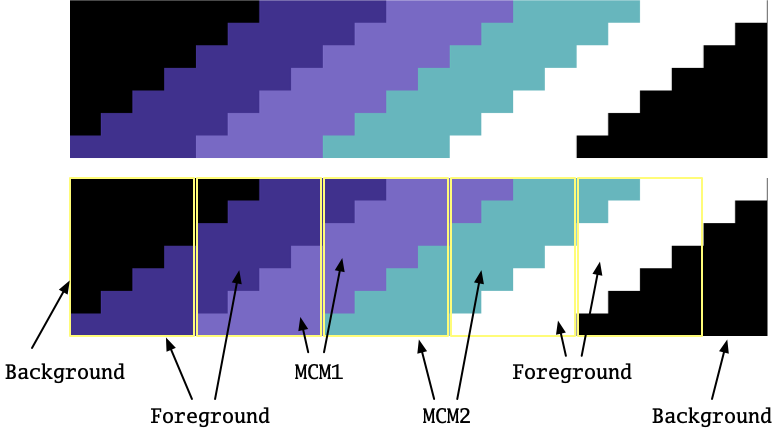

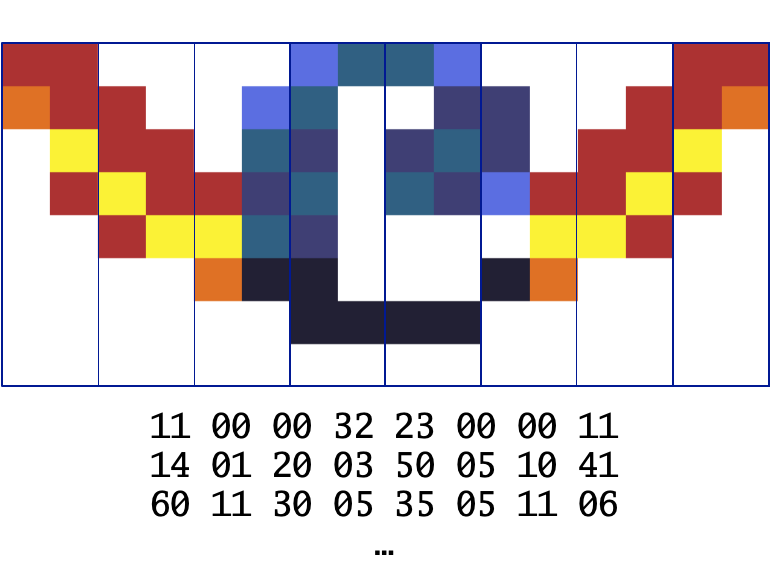

I left all of the foreground colors white in that example, but we could have proceeded to assign different foreground colors to each 8x8 patch, within the first 32 palette entries. Clever pixel artists know how to hide the color transitions between character boundaries. This gets especially interesting in combination with Low-res Multicolor Mode, like so:

In this example, the background color and two MCM colors are the same for every character on the screen, requiring careful planning to blend them with individual character foreground colors. And MCM doubles the visible width of the character pixels, potentially giving those characters a chunky look. Four possible colors per character provides more options, within these limitations.

Introducing Full Color Mode

The MEGA65 can take this to the next level. In Full Color Mode (FCM), the VIC-IV can assign a different palette entry to each high resolution pixel of a character in a character set. Instead of one bit per pixel selecting between the character’s foreground color or the screen’s background color, FCM uses one byte per pixel. Value $00 is still the background color, and $FF is the character foreground color. Values $01 to $FE select the corresponding colors directly off the palette.

We started this series on character graphics with the observation that assigning a 23-bit color value to every pixel would be impractical. It uses too much memory, and by extension is too slow to update. A 640 x 200 screen with 23 bits for every pixel would require 359.375 kilobytes—nearly all of the MEGA65’s chip RAM for a single screen.

Full Color Mode strikes a balance: it’s still character graphics, and it’s still indirectly specifying the 23-bit color with an 8-bit palette. A program like a game looking to update the display quickly can still do so with minimal memory changes, using references to character tiles. To perform our full-screen bitmap trick with 80 x 25 = 2,000 character codes, FCM would demand 64 bytes per character, or 128,000 bytes (125 kilobytes) of character set graphics data. That’s still a lot of memory, but it’s doable.

Important facts about Full Color Mode

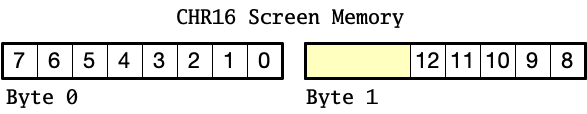

There are two important things to know about Full Color Mode. The first is that FCM is a feature of Super-Extended Attribute Mode, and requires that CHR16 be enabled.

The second important thing to know is that in Full Color Mode, screen memory does not store screen codes. Instead, it stores the absolute address of the 64 bytes of character data. CHARPTR is ignored for characters referenced in this way. For example, a screen code of $1000 (4096 decimal) refers to 64 bytes at address $1000 x $40 = $4.0000.

A character address must be aligned to a 64-byte boundary: screen memory stores the address divided by 64. With CHR16 enabled, there are 13 bits of screen memory per character, with a maximum character address of $1FFF x 64 = $7FFC0 – $7FFFF. MEGA65 chip RAM only goes up to $5FFFF, so you effectively have all of chip RAM to store full-color graphics character tiles.

I’m calling this out as important because it’s a common tripping point for developers learning FCM for the first time. This absolute address behavior is described in the manual, but the current state of this information is a series of brief paragraphs, so it’s easy to miss.

FCLRHI and FCLRLO

To enable FCM for screen codes 0 to 255, set register FCLRLO bit 1 of address $D054. To enable it for screen code 256 and higher, set register FCLRHI $D054 bit 2. Enabling FCM changes the interpretation of the affected screen codes to absolute 64-byte-aligned addresses.

Having separate FCM switches for lower and upper screen codes makes it easy to support both traditional character sets and full-color graphics on the same screen. A common configuration is to keep FCLRLO clear and only set FCLRHI. This way, screen codes 0 to 255 continue to refer to a monochrome character set pointed to by the CHARPTR register, and screen codes 256 and above refer to absolute addresses $4000 and above.

FCLRLO is therefore not particularly useful. All it does is enable the ability to refer to full-color character data at addresses $0.0000-$0.3FFF, which is not typically where a program would keep graphics data. And it trades away access to a monochrome font, such as the PETSCII font or a custom text font.

Implementing Full Color Mode

FCM is a feature of SEAM, and requires that CHR16 be enabled: set bit 0 of $D054. As we saw last Digest, this doubles the screen memory and color memory for each character to two bytes each. This also requires setting LINESTEP D058-D059 to twice the number of characters in each line (e.g. 160 bytes for 80 characters). We can’t reliably use the KERNAL screen editor’s default memory location for this, so we set SCRNPTR D060-D063 to somewhere more useful.

100 REM === Enable CHR16. Set LINESTEP to 80 x 2 = 160.

110 SETBIT $D054,0

120 WPOKE $D058,160

130 REM === Set SCRNPTR to $5.0000. Remember previous setting.

140 S1 = WPEEK($D060) : S2 = WPEEK($D062)

150 WPOKE $D060,$0000 : WPOKE $D062,$05

For this example, let’s use FCLRHI only, and leave FCLRLO clear, so we get the best of both worlds. Set bit 2 of $D054.

160 REM === Set FCLRHI.

170 SETBIT $D054,2

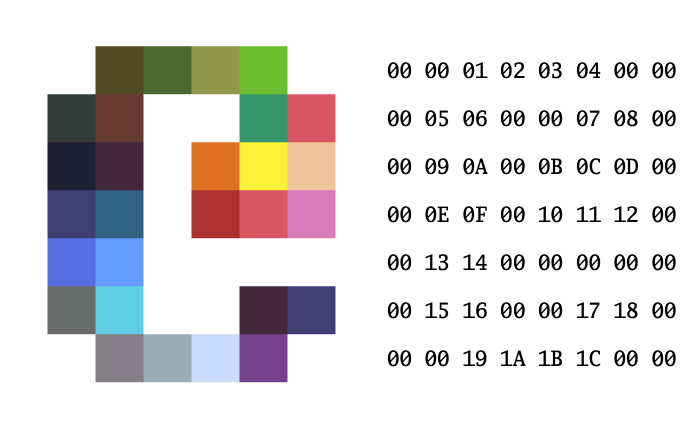

Here’s the colorful @ symbol, written to address $4.0000.

180 REM === FCM character

190 RESTORE 1000

200 FOR I=0 TO 63

210 READ V

220 POKE $40000+I,V

230 NEXT I

1000 DATA 0, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 0, 0

1010 DATA 0, 5, 6, 0, 0, 7, 8, 0

1020 DATA 0, 9,10, 0,11,12,13, 0

1030 DATA 0,14,15, 0,16,17,18, 0

1040 DATA 0,19,20, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

1050 DATA 0,21,22, 0, 0,23,24, 0

1060 DATA 0, 0,25,26,27,28, 0, 0

1070 DATA 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

And here’s a custom palette that matches my diagrams above. If you’re following along, you can skip this part, and just see the result in the default system palette.

Remember that 8-bit color component values need the nibbles swapped before storing. Here, I’m swapping them in the POKE statement, so that my DATA statements look like the actual RGB values.

240 REM === Custom palette

250 RESTORE 1100

260 FOR C=0 TO 28

270 READ R,G,B

280 POKE $D100+C,((R AND 15) << 4) OR (R >> 4)

290 POKE $D200+C,((G AND 15) << 4) OR (G >> 4)

300 POKE $D300+C,((B AND 15) << 4) OR (B >> 4)

310 NEXT C

1100 DATA 255,255,255

1110 DATA 82, 75, 36, 75,105, 47

1120 DATA 143,151, 74, 106,190, 48

1130 DATA 50, 60, 57, 102, 57, 49

1140 DATA 55,148,110, 217, 87, 99

1150 DATA 34, 32, 52, 69, 40, 60

1160 DATA 223,113, 38, 251,242, 54

1170 DATA 238,195,154, 63, 63,116

1180 DATA 48, 96,130, 172, 50, 50

1190 DATA 217, 87, 99, 215,123,186

1200 DATA 91,110,225, 99,155,255

1210 DATA 105,106,106, 95,205,228

1220 DATA 69, 40, 60, 63, 63,116

1230 DATA 132,126,135, 155,173,183

1240 DATA 203,219,252, 118, 66,138

Clear screen and color memory at our custom SCRNPTR location of $5.0000, remembering that both screen and color codes are two bytes now. Screen code 32 still refers to a PETSCII space, because FCLRLO is clear.

320 REM === Clear screen

330 FOR I=0 TO 3999 STEP 2

340 WPOKE $50000+I,32

350 WPOKE $FF80000+I,0

360 NEXT I

370 REM === Set background and border to color 0,

380 REM === which in this custom palette is white.

390 BACKGROUND 0:BORDER 0

Lastly, draw a brief message, and our custom character:

400 REM === Draw characters

410 RESTORE 1300

420 FOR I=0 TO 18 STEP 2

430 READ C

440 WPOKE $50000+I,C

450 POKE $FF80000+I+1,1 : REM Color bits are in the high byte

460 NEXT I

470 WPOKE $50000+(2*80*2)+4,$1000 : REM $40000/$40

1300 DATA 8, 5, 12, 12, 15, 32, 6, 3, 13, 33

Let’s round out the program by waiting for a keypress, then restoring the original screen settings.

480 REM === Wait for spacebar

490 GETKEY A$:IF A$<>" " THEN 350

500 REM ==== Restore palette, FCLRHI, CHR16, LINESTEP, and SCRNPTR.

510 PALETTE RESTORE

520 CLRBIT $D054,2:CLRBIT $D054,0:WPOKE $D058,80

540 WPOKE $D060,S1:WPOKE $D062,S2

550 END

Nibble Color Mode: The Search for More Memory

256 colors is a luxury, but sometimes memory is a luxury we can’t afford. And yet it is still useful to be able to use many colors in a single character. What else can we trade?

In Nibble Color Mode (NCM), four bits describe a pixel, instead of eight. That gives us a respectable 16 colors to choose from for each pixel in a given character. Each pixel uses half as much memory as Full Color Mode.

Hang onto your butts, because there’s a lot to know about Nibble Color Mode. We’ll take this one thing at a time.

NCM is a feature of a character

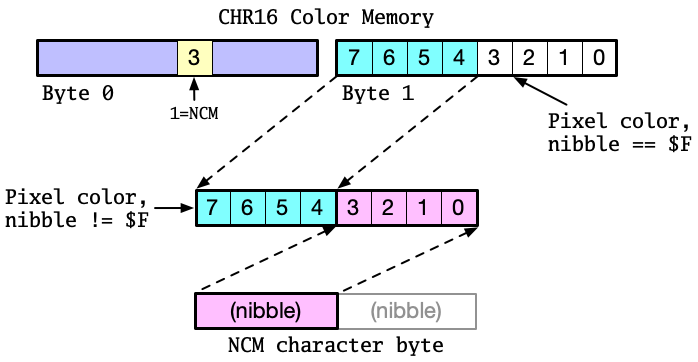

Nibble Color Mode is not a system mode. It is a feature of an individual character, while in Full Color Mode. You tell a character to interpret its character set data as NCM instead of FCM by setting bit 3 of its color RAM value.

Combined with keeping FCLRLO clear, this means you can mix monochrome (lower non-FCM chars), full color (upper FCM chars, color bit 3 clear), and nibble color (upper FCM chars, color bit 3 set) characters, all on the same screen.

The low nibble is the left pixel

With a character in Nibble Color Mode, each byte represents two horizontally adjacent pixels. The “lower” nibble in bits 0-3 of the character data is the left pixel, and the “upper” nibble in bits 4-7 is the right pixel. This is backwards from how we normally think of pixel order in monochrome pixel data, where the most significant bit is the left-most pixel.

NCM characters are 16 pixels wide

A character in Nibble Color Mode still uses 64 bytes to describe all of its pixels, 8 bytes per row. With two nibbles per byte, an NCM character is 16 pixels wide instead of 8! These are normal-sized pixels, not halved or doubled. The NCM character simply takes up more space on screen because it has more horizontal pixels. The character at the subsequent screen and color memory location starts at the horizontal position where the previous character left off.

This is wild! For the first time in this series, we have to think of a character taking up a variable amount of space on a row depending on its properties. No longer can you say for sure that a character described at a given memory address has a given horizontal coordinate: its actual position depends on previous characters in the row.

And here is our first clue as to the usefulness of the LINESTEP register. Each row takes up LINESTEP number of bytes in memory. In normal text mode, a row of 80 characters needs one byte per character, so LINESTEP = 80. In CHR16 mode with monochrome or FCM characters, a row of 80 characters needs two bytes per character, so LINESTEP = 160.

If you have a screen full of NCM characters, 640 pixels per row and 16 pixels per character means you have 40 characters per row, each taking two bytes. In this case, you could set LINESTEP to 80, and avoid leaving a bunch of unused memory at the end of each row. You could even mix character modes on a row, and as long as you have a reliable maximum number of non-NCM characters, you could set LINESTEP accordingly.

In later Digests, we will see other amazing things that the VIC-IV can do with its row-wise rendering, and find other uses for LINESTEP.

NCM can pick colors from any group of 16

The actual color of a pixel is a combination of the four-bit pixel data and the color value for the character in color RAM. The upper four bits of the color data for the character (bits 4-7 of color byte 1) are used as the upper four bits of the color value, and the character data nibble is the lower four bits. This allows multiple NCM characters to access all 256 colors of the palette on the same screen, with the limitation that only 16 at a time can be used for a given 16 x 8 NCM character.

If the nibble value is $F, the color of the pixel is the full 8-bit color RAM value for the character.

That sounds complicated, but it’s quite powerful. We can use techniques similar to the VIC-II Low-res Multicolor Mode (MCM) blending trick we saw earlier to hide differences between characters, with many more color options at our disposal.

Converting PNG images to character sets

More powerful graphics features demand richer graphics data. You’re more than welcome to stick with the old-school methods of graph paper and DATA statements. To fill a screen with color, you’re more likely to want to use graphics editing tools and image data converters.

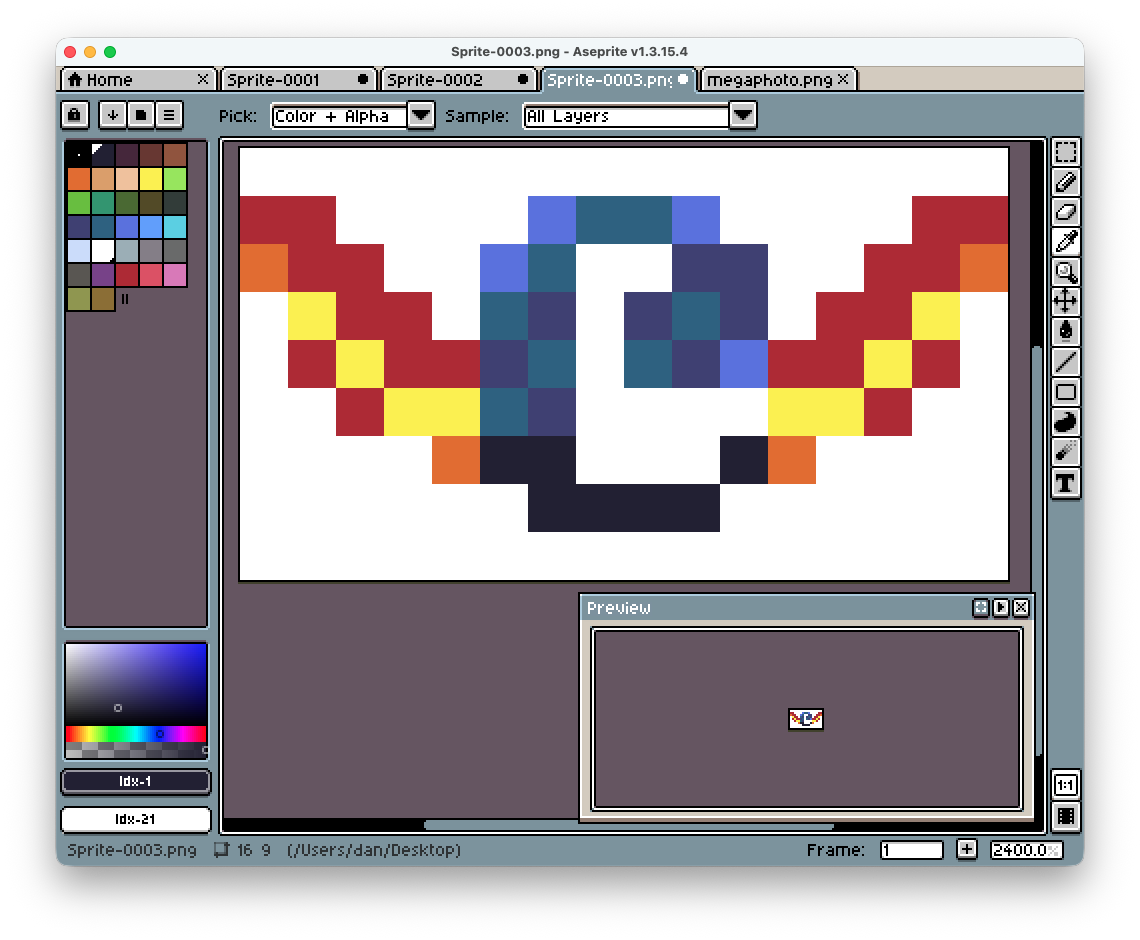

By far the most popular graphics editor for retro-style pixel graphics is Aseprite. It’s available for Windows, macOS, and Linux, for a lean one-time $20 purchase that’s worth every penny. Alternatively, you can opt for the free LibreSprite, which has a common origin with Aesprite. Aesprite gives you fine control over pixels and palettes, and allows you to animate your creations and export animation frames in a sprite sheet.

Tips for using Aseprite for MEGA65 graphics, and for conversion to other vintage or retro-style computers:

- Set color mode to “indexed.” This tells Aseprite to save pixel data as palette entry numbers, and not RGB values for each pixel. Open the Sprite menu, Color Mode, then select Indexed.

- Set up your palette to match your desired MEGA65 graphics mode. If you’re using Full Color Mode, it’s easiest to establish a 256-color palette directly in Aseprite, and use the same palette for everything. You can save and load palettes from the Options button-menu above the palette on the lefthand side.

- Set image dimensions in multiples of 8, and draw tiles and sprites on 8-pixel boundaries, so you know your images align to characters.

- Export using the PNG file format, a lossless format that includes palette and image data in one file, when in indexed color mode.

I’d love to nerd out on the PNG file format here like I did with IFF, but you can read the Wikipedia article for details. Instead, we’ll use the PyPNG Python library to extract the data. To install this library from PyPI using pip:

python3 -m pip install pypng

In Python, access the image data of the PNG exported from Aseprite like so:

import png

reader = png.Reader(filename='Sprite-0001-export.png')

width, height, pixels, metadata = reader.read()

If everything exported as expected, metadata['palette'] contains the RGB values for each palette entry, in order, as a tuple of three byte values. You can confirm that metadata['bitdepth'] is 8, which says each of the color values in the palette is a byte.

The pixels value is a list of pixel rows, where each row is bytearray of palette entry numbers the width of the image. This is where most of the conversion work needs to happen: for FCM characters, the bytes need to be rearranged as 8-by-8 character tiles, where each tile’s bytes are organized row-wise top to bottom.

A simplified PNG conversion example

Here is my attempt at the simplest possible logic to convert a photograph to an almost-full-screen FCM display. I resized the photo to 640 x 192 image, so there’s enough room in banks 4 and 5 for both the FCM character data (640 x 192 = 122,880 bytes) and the CHR16 screen data (80 x 25 x 2 = 4,000 bytes). I exported the image with 8-bit indexed color and 256 palette entries.

Then I used the following Python script to prepare the palette and image data as separate binary files. The png library provides palette data as 256 (r, g, b) tuples; the script swaps the nibbles for each value, then stores them as 256 reds, 256 greens, and 256 blues, to the file mppal.dat. This is the format expected by the palette registers starting at $D100.

To convert 192 pixel rows of 640 palette entries into FCM data, the script considers each 8 x 8 rectangle in character rows, writing the character image data in order to the file mpdata.dat.

import png

FNAME_INPUT = 'megaphoto.png'

FNAME_PAL = 'mppal.dat'

FNAME_DATA = 'mpdata.dat'

reader = png.Reader(filename=FNAME_INPUT)

width, height, rows, info = reader.read()

rows_lst = list(rows)

def nibble_swap(v):

return ((v & 0x0f) << 4) | ((v & 0xf0) >> 4)

reds = [nibble_swap(t[0]) for t in info['palette']]

greens = [nibble_swap(t[1]) for t in info['palette']]

blues = [nibble_swap(t[2]) for t in info['palette']]

with open('mppal.dat', 'wb') as f:

f.write(bytes(reds))

f.write(bytes(greens))

f.write(bytes(blues))

with open('mpdata.dat', 'wb') as f:

for ychar in range(height // 8):

for xchar in range(width // 8):

for y in range(8):

for x in range(8):

b = rows_lst[ychar * 8 + y][xchar * 8 + x]

f.write(bytes([b]))

I put mppal.dat and mpdata.dat onto a D81 disk image, along with the following BASIC program. I’m using BLOAD to load the data files. BLOAD does not support loading data directly into registers, so I load the palette file into a temporary memory location first then copy the data into the registers. The character data is loaded to address $4.0000, with just enough room for screen memory at address $5.F060.

The program fills screen memory with consecutive character addresses starting at $4.0000—similar to the monochrome bitmap example from the last Digest. It fills color memory with $FF00, so that any pixel from the image using color $FF actually uses palette entry $FF. Recall that a pixel valued as $FF is actually colored with the palette entry in color memory for the character, so color memory needs to be filled with high bytes of $FF to match the intent of the image.

Because some color memory bits are treated as character attributes (blink, underline, reverse) by default, you must disable character attributes in this mode. You can do this by setting the ATTR register, bit 5 of $D031. All registers at this address trigger the “hot register” mechanism, so it’s important to do this early in the program, or disable hot registers per the instructions in the Compendium. (To save space here, we’ll discuss hot registers another time.)

100 REM === Set ATTR to enable 8-bit color memory (no attributes).

110 SETBIT $D031,5

120 REM === Enable CHR16. Set LINESTEP to 80 x 2 = 160.

130 SETBIT $D054,0

140 WPOKE $D058,160

150 REM === Set SCRNPTR to $5.F060. Remember previous setting.

160 S1 = WPEEK($D060) : S2 = WPEEK($D062)

170 WPOKE $D060,$F060 : WPOKE $D062,$05

180 REM === Set FCLRHI.

190 SETBIT $D054,2

200 REM === Load image chars to $4.0000.

210 BLOAD "MPDATA.DAT",R,P($40000)

220 REM === Load palette to temp location, then copy.

230 BLOAD "MPPAL.DAT",R,P($1E000)

240 FOR I=0 TO 767:POKE $D100+I,PEEK($1E000+I):NEXT I

250 REM === Fill screen.

260 FOR I=0 TO 1919 : REM Stop at 24 rows.

270 WPOKE $5F060+I*2,$1000+I

280 WPOKE $FF80000+I*2,$FF00

290 NEXT I

300 FOR I=1920 TO 1999 : REM Fill row 25 as empty.

310 WPOKE $5F060+I*2,32

320 WPOKE $FF80000+I*2,0

330 NEXT I

340 REM === Set background and border to color 0.

350 BACKGROUND 0:BORDER 0

360 REM === Wait for keypress, then reset.

370 GETKEY A$:IF A$<>" " THEN 370

380 PALETTE RESTORE

390 CLRBIT $D054,2:CLRBIT $D054,0:WPOKE $D058,80

400 WPOKE $D060,S1:WPOKE $D062,S2

410 END

Of course, both the Python script and the BASIC loader could be expanded to accommodate images of any dimension and palette size. You could even invent a file format that includes dimensions, palette, and image data in a single file, ready to use with a general purpose image viewer based on FCM character graphics.

A general purpose image converter would be nice, but I find it useful to know how to customize the conversion process. For example, a program using NCM graphics would need to know more about what should go into color memory, or how 16 x 8 NCM characters are organized on screen. A game with tiles or animations would need to know how the sprite sheet is arranged. Tools like Aseprite combined with custom data management are a part of a powerful retro gamedev workflow.

We’re making great progress on our character graphics series, but there’s still some ground to cover! The MEGA65 has more tricks up its sleeve for more colors, fancier text rendering, and arcade graphics techniques. It’ll take a few more issues to cover it all.

A quick note about the newsletter schedule. You may have noticed that I haven’t quite kept up a monthly cadence over the last few months. I know you’re OK with it, and I’m OK with it too, I just want to acknowledge it. As long as this Digest is a community resource, I owe it to you to at least send out community news on a regular basis. I’m planning one more issue in the 2025 calendar year. For 2026, I’m considering adjusting the format to post community news and feature articles separately. Expect some experimentation.

This Digest is supported by cool people. If you’re a cool person, consider becoming a supporter for the new year. Visit: ko-fi.com/dddaaannn

Thanks all!

— Dan