IFComp 2014 Prize Game

I donated six prizes to the Interactive Fiction Competition 2014. As a surprise for the winners that selected my prizes, I made a little puzzle chain game. Here’s how it went.

The idea

The Interactive Fiction Competition is an annual celebration of new works of text-based interactive fiction by the hobbyist community. Authors write text games and interactive stories for the competition, and then everyone plays and rates the games. The authors of the top rated games get to pick from a pool of prizes donated by the community.

I never have time to actually write a game to enter, so I usually just donate prizes. This year, I donated one copy of each of several books relevant to interactive fiction:

- Inform Designer’s Manual, by Graham Nelson (Amazon)

- Creating Interactive Fiction with Inform 7, by Aaron Reed (Amazon)

- To Be or Not To Be, by Ryan North (Amazon)

- Meanwhile, by Jason Shiga (Amazon)

- What Lies Beneath the Clock Tower, by Margaret Killjoy (Amazon)

- Twisty Little Passages, by Nick Montfort (Amazon)

I submitted my intention to donate early in the year, with the competition scheduled to finish by December. As time went on, I started to think, books are nice and all, but these are pretty obvious choices. It’d be nice to make these prizes a bit more posh, as a surprise for anyone expecting just a book.

Since I would be sending the prize directly to each recipient, I’d know who was selecting each prize and which game they entered. Maybe I could include a cheesey “Certificate of Achievement” printed on on certificate paper, with an Olde English headline and the author’s name and the title of their game on it. I could also include a personalized cover letter, congratulating each winner and telling them what I liked about their game.

I mulled this over for a few more weeks. And then I thought, sure a certificate and a letter are neat, but you know what’d be really cool is if the prize package was itself some kind of game. I immediately had a bunch of overly ambitious ideas for a small alternate reality game, a world beneath the surface of these unusual artifacts they’d receive in the mail, a game designed exclusively for six specific people to play.

Scaling it back

I always enjoy the early phase of a project where all crazy ideas seem possible (who doesn’t), but I knew I’d have to start pulling it back to something plausible if I actually wanted to, you know, do it. I can’t claim much experience with game or puzzle design, artifact fabrication, or even fiction writing. I say this not to count myself out: the IF community flourishes with enthusiastic novices working in all of these fields. But everything takes more time when you’re trying something new, and I knew I’d have little time to work on this before the prizes would need to be sent out. I’d have to stick with concepts that I could execute in only a few weekends of work.

I wanted to keep the coy, subcutaneous aspect of an ARG, where there is no explicit declaration that a game is present, even if it’s otherwise obvious from clues. But I was willing to sacrifice everything else, even the possibility of a story world. Of course, it wouldn’t be an ARG without a story world. But a puzzle box looks like a regular box, at first.

I decided on a short chain of puzzles that would be lightly buried in all three aspects of the prize package: the book, the certificate, and the cover letter. Each puzzle would unlock the next, finally revealing some kind of message. Writing a satisfying final message was the hardest part of the design. I wanted to give the last step a sense of finality, to make it obvious and satisfying that you’ve reached the end without just saying, “The End!” I worked from the principle that the beginning of the puzzle should pose some kind of question, and the decoded message would reveal the answer to that question. I considered various story-based ideas, but also other call and response structures: a joke set-up and punchline like you’d find on a popscicle stick, or just an obscured element that is visible before the first step and made clear by the final step.

At my peril, I also wanted all six prizes to fit together somehow, to encourage the prize winners to find each other (such as on the Interactive Fiction Forum) and collaborate. Collaboration would allow players to work around difficult (or broken) puzzles and get to the end, and public collaboration would allow me to observe and drop hints if needed. Finding other players could be a puzzle in and of itself, and the buried but discoverable fact that I donated more than one prize could be a clue.

Of course, requiring players to find each other and collaborate was risky. If any player chose not to participate or didn’t know how to contact the others (or that there were others to contact), I’d need contingency plans to degrade gracefully and allow me to jump in and fill the gaps.

The sequence

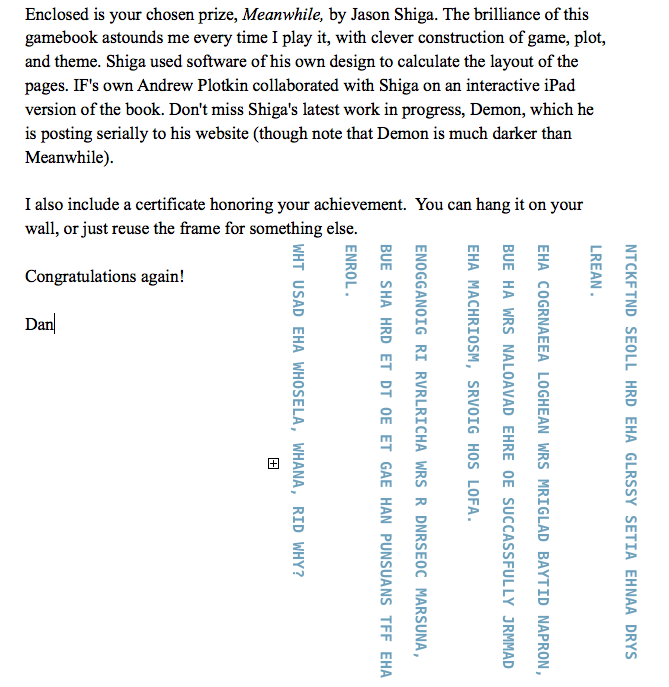

Each player receives their chosen book prize, along with a personalized letter and a certificate in a frame.

The letter consists of a cordial message in black ink. This message doesn’t contain puzzle elements or refer to the fact that there is a puzzle. On the same page, printed sideways in blue ink with a different typeface, is an encoded message of English letters.

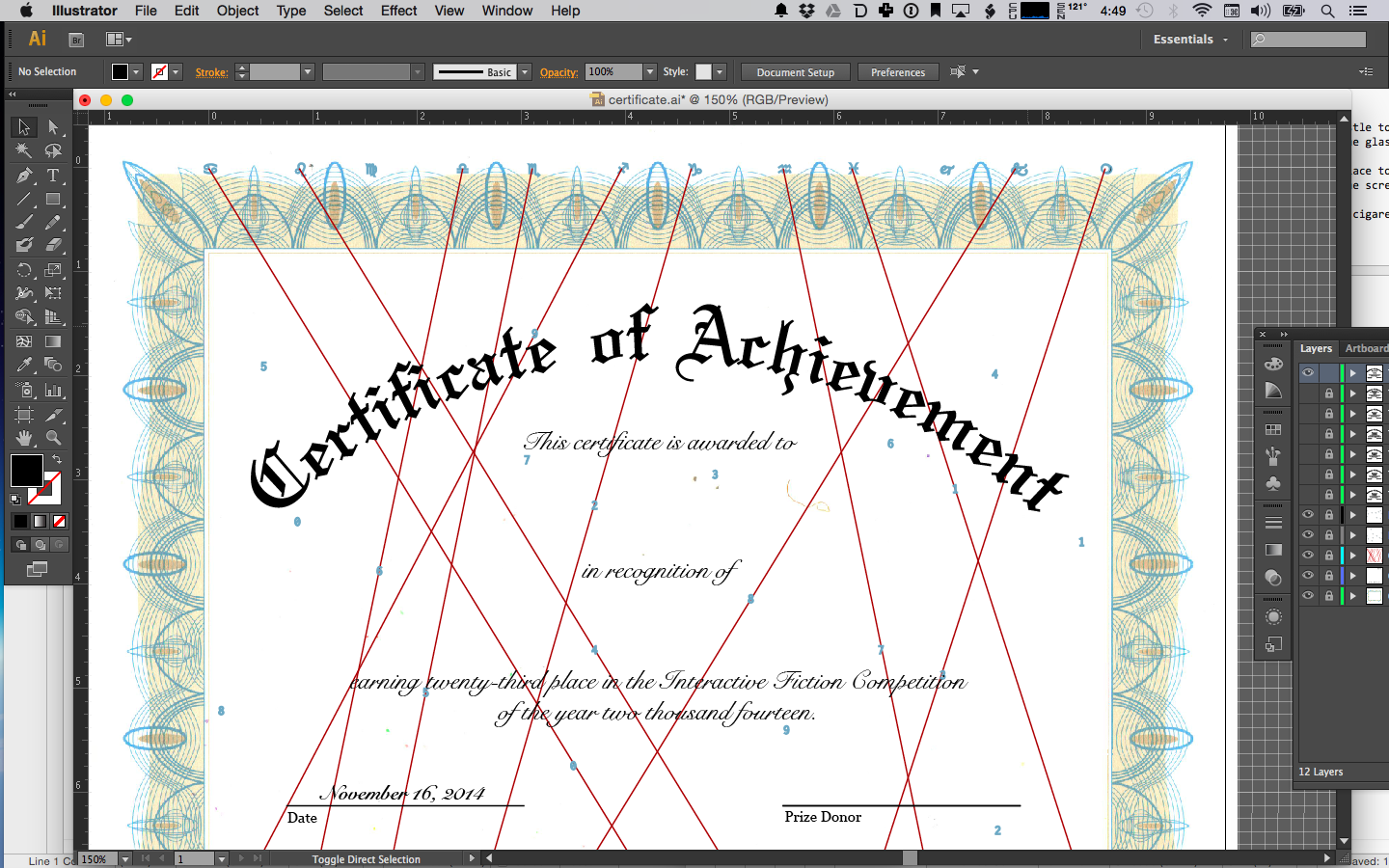

The certificate has a formal message of congratulations with the winner’s name and game title in black ink. In blue ink, symbols run along the top and bottom of the ornate certificate border, and the digits 0 through 9 are scattered, apparently at random, across the entire sheet.

Step zero is to recognize that a puzzle game is included in these elements. (I figured this part would be trivial, especially for game authors.) The rest of the sequence is as follows:

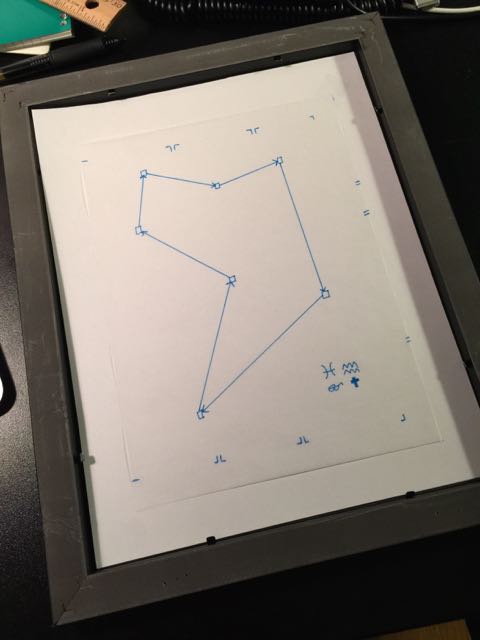

- Detach the frame backing, as if you are going to remove the certificate from the frame. (I hoped this would be a natural step toward investigating the certificate, and this step is hinted gently in the letter.) This reveals a new artifact: a diagram with arrows, boxes, and symbols, drawn on a piece of tracing paper.

- Match the symbols on the diagram to those on the certificate. The diagram’s symbols are arranged in two rows. The top row’s symbols all appear in the top border of the certifiate, and the bottom row’s symbols in the bottom border. Reading the diagram’s symbols as top and bottom pairs, find the top symbol and the bottom symbol on the certificate, then hold a straightedge between them. Each pair crosses exactly one digit, and locating all pairs reveals a multi-digit integer.

- Notice that the tracing paper on which the diagram is drawn is the same size as a page of the book. Locate the page in the book whose number is the multi-digit integer encoded on the diagram by the symbols. Place the tracing paper over the page, and line up the edges and other elements. Doing so puts specific letters in each of the boxes, with arrows pointing between the boxes.

- For each letter in the encoded message, if the letter appears in a box in the overlaid diagram, follow the arrow to the next box, then replace the letter in the message with the letter in the new box. The message decodes to English words, consisting of two or three statements and a question.

- Recognize the message as being an excerpt from a logic puzzle, sometimes called a “logic grid puzzle” because you usually use a grid diagram to solve it. Notice that the question cannot be answered from the statements.

- Discover that multiple authors received similar prizes, but the identities of those authors are not disclosed. Attempt to make contact in a public online forum. Collaborate to help all players decode their messages, then combine the messages to form the complete set of clues for the logic puzzle. Solve the puzzle to answer the question posed in the message. (Players each receive different clues, but the same question.)

The intent is for the player to feel satisfied with having decoded the English sentences presented in step zero, but be curious about why the last puzzle is incomplete. I figured it’d be great if players go straight to the forum to look for a discussion thread or start one, but most likely players would try to contact me first, possibly by contacting the IFComp coordinator (since my contact info is not on the IFComp website). I planned to wrangle players to the forum and post missing clues proactively if not all six players completed the sequence.

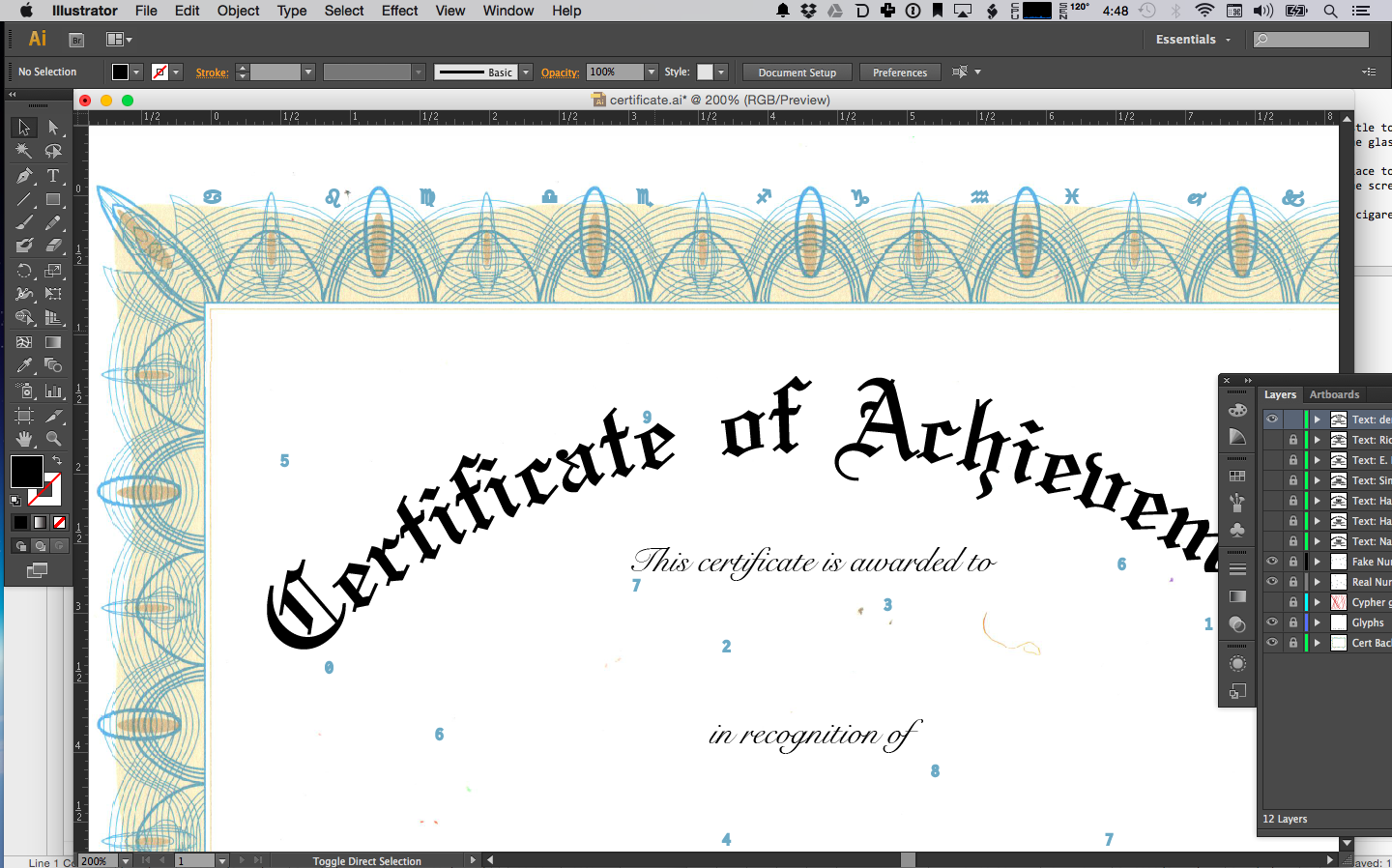

The certificate

You can buy “certificate paper” at Office Depot (an office supply warehouse chain in the United States) and make reasonably nice looking certificates on a laser printer. Packets of this stationary even include a gold sticker in the shape of a multi-pointed star, for extra class.

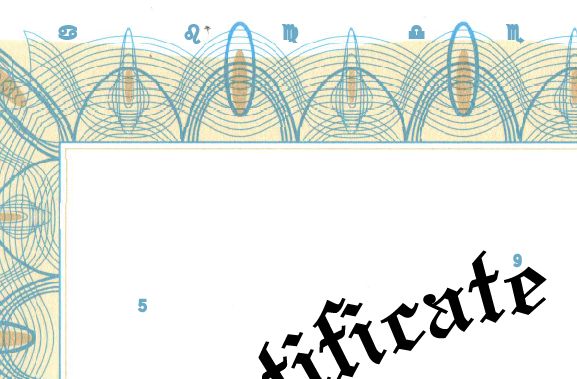

I wanted the cryptic symbols to appear as if they were part of an ornate border. I selected paper with an appropriate border, then I scanned a blank page into Adobe Illustrator. I did some test prints to get the printer output to align with the paper. I used the scan as a background layer so I could position the elements of the design.

I selected the blue color from the scan so that the symbols would look like they were part of the border design. I didn’t want to hide the symbols, only to separate them from the non-puzzle elements. Using a matching color for the coded message in the letter was an afterthought, but a good one.

The symbols are straight out of Wingdings, selected for legibility. I downloaded a free Olde English font from some random website for the “Certificate of Achievement,” and looked at various examples of certificates in a Google Image search for layout ideas. The script font is Snell Roundhand, the non-script font for the names and other elements is Georgia, and the fixed width font for the numbers is Inconsolata.

I used a non-printing layer to draw guidelines between the symbols for placing the numbers. I had to balance the degree to which lines crossed with avoiding making too many ambiguous regions in the middle where I could not place numbers. I established valid encodings for all ten digits, then placed a second set of ten decoy digits in locations that could not be mistaken for being on any line.

My design ended up with too many elements on the page to use the gold star stickers. Otherwise the result was quite satisfying, especially once printed on the stationary and set in an 8-1/2" x 11" picture frame.

There was one hiccup during assembly. I had all six the certificates assembled in their frames and ready to go before I realized that I forgot to sign them. What good is a certificate if it isn’t made official with a signature? I opened them all up, signed on the lines, and put them back together.

The overlay key

I wanted to involve the book prize in the puzzle somehow without physically modifying the book itself. Having clues come from an element that I don’t “control” would contribute to the ARG-style sleight of hand: the key is “in” the book. An overlay that points to elements on a page is a blunt way of doing this, but I never intended to be subtle. I hoped it’s fun enough just to figure it out, and it doesn’t need to make sense.

For some reason, my initial vision of the overlay was a black piece of paper with holes in it. It’s obvious in hindsight that this would be difficult. The holes and edges would have to fit exactly to select specific letters off of a page of text. I considered making a scale replica of the page to locate the letters, but I didn’t want to crease the bindings of the books trying to get a flat scan. I tried measuring letter locations with an L-square, but it was too time consuming. I managed to get a demo of black paper working with good placement of the holes, only to realize that the opaqueness of the overlay made it impossible for the player to verify that it was placed correctly. Two millimeters to the left and the key would select the wrong letters. I considered using only first letters of words to make the target letters easier to hit.

I tried using tracing paper and hand-drawing boxes around the letters, with the intent of using it as a guide to cut holes in black paper. But the tracing paper solved the placement verification problem well enough, and also afforded other opportunities to guide the player toward correct alignment. So I dropped the black paper entirely and just used the tracing paper as the overlay. It’s less mysterious an object, but I’d rather this part work well, since it’s a major gate to the rest of the game.

It was my 9-year-old that pointed out one potential misunderstanding at this stage. It looked to him as if the overlay goes on top of the certificate, and the boxes go over the numbers and symbols. This did not occur to me at all. I hoped that this dead end would make the real solution more satisfying, but I was surprised that I didn’t even think of this possibility.

The overlay specifies the corresponding page using a page number encoded with the symbol cypher. I was so proud of this idea until I realized that one of the books, Meanwhile, doesn’t have page numbers. I decided to choose an early page for the cypher, and implicitly ask the player to count pages starting from the first story page (where the numbering would normally start). I tried to include other confirmation and alignment marks on the tracing paper to compensate. In theory, for this one you could skip the symbol key and just try to find a matching page, but I suspected the symbol key would still be useful.

I did not get a chance to playtest this part of the game with someone else. I tried it multiple times with each key to see if I could anticipate potential problems with the overlay. I still wasn’t sure it would work by the deadline, and I considered scrapping it in favor of identifying letters via numbers, encoded as symbols: page, line, word, letter. That didn’t sound as fun, and in the end, I decided to take my chances with the overlay.

Another assmebly disaster narrowly averted: I nearly shipped one of the packages with the overlay key stuck inside the book instead of in the frame. That’s what I get for working on my hobby projects in the middle of the night.

The cypher

T → I → R → O → A → E → N → T

NHA SCIAWDITVAI COMA TE HOEDY DRWE BY NHA BOBBLTEG BIRRK.

| | || || || | | || || | | | | | || |||

v v vv vv vv v v vv vv v v v v v vv vvv

THE SCREWDRIVER CAME IN HANDY DOWN BY THE BABBLING BROOK.

I went through various ideas of how to use elements of a book page as a cypher for the message. I was concerned that the message would be long, and I didn’t want to burden the player with a 26-character substitution cypher over a long message. I also thought it might foil cracking the message with brute force if not every letter participated in the cypher. (I was wrong, but more on that later.)

I chose the seven most used letters in English, ETAONRI, as the elements of the cypher, thinking this would be enough to obscure the message without making decoding it from the key a chore. I did some computer-assisted tests with messages and cyphers of various lengths. It turns out the top seven most frequent letters account for more than half of letters used, so I only cut down the amount of work by that much. I ran through the decoding process manually on paper just to see how bad it was. I was confident it’s less of a drag if you don’t know what the message is supposed to say.

The letters substitute in a circular chain. I chose this to give the boxes-and-arrows diagram on the tracing paper a map-like appearance, and for no other reason.

I also chose to give each player the letter chain in a different order. This was probably unnecessary. I think in the early stages I assumed the key would have to be specific to the book and page I selected for each player, not realizing that almost every letter of the alphabet appears many times on a typical page and this would not have been a problem. I was also imagining it’d be a fault if you could use one player’s key to decode another player’s message. But in preventing this, I deprived players of collaborating to work around difficulties with the overlay. The certificates all have the same symbol key, and there’s not really a good reason all players shouldn’t have the same letter cypher. It’s potentially interesting that all six cyphers use the same seven significant letters, and that might be an advanced path to correcting a broken clue.

Naturally, I was paranoid about making sure all of the elements in each package matched, and tried very hard to make sure that the certificate, key, book, cypher, and letter all ended up in the same box.

The logic puzzle

I had more ambitious ideas for the “payload” of the puzzle. Once I reached the idea that the decoded message could itself be some kind of text game, I couldn’t shake it. I eventually talked myself down to doing a logic puzzle, with the clues distributed across the players. This kept the messages short and still resulted in something game-like.

A logic grid puzzle consists of a set of clue statements, and usually includes a question that needs to be answered, as if the statements answer the question in some indirect way. The terms used in the statements and the question describe a story world, with a fixed number of dimensions (people, houses, hats, pets) and an equal number of terms in each dimension. The Zebra puzzle is the most canonical example, with clues such as “The Ukrainian drinks tea,” and “Coffee is drunk in the green house,” from which the player would understand that there are people with different nationalities (Ukrainian) in different houses (green) drinking different beverages (tea, coffee). It is stated or implied that each term in each dimension is exclusive to one term in each of the other dimensions. So the player can infer that the Ukrainian does not also drink coffee, and therefore the Ukrainian is not in the green house and must be in one of the other houses described by the clues.

The player’s task is to correctly interpret the clues to:

- Determine the dimensions and terms of the story world

- Derive as many facts about the story world as possible from each clue

- Infer facts not stated directly by the clues to form a complete description of the story world consistent with the clues, where a complete description associates all of the terms in every dimension

I’d never actually written one of these before, and I went hunting for examples to figure out what to expect. The zebra puzzle has five dimensions, five terms each (a 5-by-5 puzzle), and is stated in 15 clue statements with two or three terms in each statement. The logic puzzles I remember from childhood never got as large as 5-by-5, and the zebra puzzle is often misattributed to Albert Einstein, so I guessed it was considered difficult by some standard. I suspected that this would probably be the right size of puzzle for my intended audience.

The Wikipedia page notes that the zebra puzzle as it was printed in Life International magazine in 1962 includes ambiguous wording that breaks the logic. This, plus the prevalence of broken logic puzzles I was able to find on the Internet, made me nervous about shipping a broken finale. I spent some time trying to build my own logic puzzle solving software so that I could verify that the puzzle I would write would have exactly one solution. Due to time pressure, I bailed on that, and considered using an existing SAT solver (such as MiniSat) for this purpose.

Finally I found Logikloeser by Johannes Singler, a browser-based tool for doing this kind of logic puzzle. In its weakest mode, it acts as a diagramming tool, and it is your job to infer information from the grid as if you were doing the puzzle on paper. In its strongest mode, you only have to enter in the facts presented by the clues, and the grid fills itself in with inferences. If you correctly and completely interpret the clue statements, the grid will fill in with the solution. If the clues are written well enough, then most players would interpret the clues the same way, and the solution found would be the intended one.

Here is the puzzle I sent to my players:

- Donatello, the scientist, and the man at the ancient temple were grateful they never had to deal with the wild boar.

- The screwdriver came in handy down by the babbling brook.

- Neither the zoo keeper nor the army general knew what to make of the android, but for some reason they trusted it.

- The luxury apartment's state of the art security system was thought to have been impossible to override.

- Ace wished he had something that made noise, but he managed it using sunlight reflected off of the object he carried.

- The former athlete pried the handle of the missile silo door with all her might, but it was no use.

- The report it filed when returning from its mission said nothing about a carnival or a necklace.

- Hannah never determined how the wild boar got in, but she was glad it didn't follow her out.

- Rockford still had the glassy stone three days later.

- The cigarette lighter was mangled beyond repair, but he was relieved that it successfully jammed the mechanism, saving his life.

- Triggering an avalanche was a drastic measure, but she had to do it to get her pursuers off the trail.

- The zoo keeper was accustomed to stealth, and he managed to distract the guard without alerting anyone to his presence.

- Jacqueline was impressed by the android's ingenuity, but not particularly surprised.

- Donatello's military training did not prepare him for this day.

- Rockford used the air vent to both enter and exit.

- After completing the task, the scientist felt a desperate need to be indoors.

Stop reading here if you want to try this for yourself. For a complete experience, use graph paper, or use Singler’s Logikloeser with a clear board and change “Draw conclusions” to “No support.”

For an easier time, try Logikloeser pre-populated with the dimensions and terms. This saves you some work, but assumes that my puzzle is written well enough that you would have found the intended dimensions, which is not a given.

I started by defining dimensions and terms, going for a text adventure theme: player characters using objects in locations to overcome obstacles. I tried to keep the terms mostly unrelated so that the solution must be inferred from the clues, and so that the clue statements would not imply false associations with accidental assumptions. I wrote solution statements, then started writing clues one at a time. For each clue, I extracted the intended facts from the clue and entered them into Logikloeser. Then I looked for holes in the grid, and tried to fill them with more clues. Once the grid was filled and the derived solution matched my solution statements, I felt confident that I had a complete set of clues.

So it was alarming to reset the grid, walk through my own clues, and end up with an incomplete grid. I tried again, added more clues, and repeated until I, the puzzle author, was getting a consistent interpretation and a complete result.

I convinced a friend to playtest this puzzle for me, and was once again alarmed that he came up with a different set of terms and dimensions, and subsequently a different solution. The biggest issue was unclear linguistic boundaries around the “locations” and “obstacles” terms. My friend was conflating these into one dimension in a way that was inconsistent with the intended solution. I did some rewriting, and added the final question, “Who used the whistle, where, and why?” to reinforce that “where” is a distinct dimension.

Most puzzles of this type limit terms to nouns and adjectives so that the terms will be legible in the clues, much like how text adventures emphasize nouns so the player understands them as game objects. I took a huge risk making one dimension contain verb clauses (“jam the mechanism,” “distract the guard,” “deal with the wild boar”). These were the most difficult to state clearly as terms, and I’m still not sure I was entirely successful. The paraphrases and oblique references I used to make the clues more fun to read only made this worse, and unrelated verb clauses (“evade the pursuers”) are easy to misinterpret. You need synonyms and pronouns to add color to the clues, and these are easier to recognize as such when associated with nouns and adjectives than with actions or situations. The zebra puzzle uses verbs as the connectors between the terms (“The Spaniard owns the dog,” “The Englishman lives in the red house”), which saves the writing from monotony.

Other tips I discovered for writing clues:

- A fact that states a positive association between two terms (“The Ukrainian drinks tea”) provides much more information than a fact that states a negative association (“The Ukrainian does not drink tea”). Clues should provide a mix of positive and negative facts for variety. Interestingly, the zebra puzzle uses only positive facts, and uses a low density of facts per statement. I’ve seen other puzzles pack more facts into fewer statements, and parsing them out is part of the game.

- If you’re filling out the grid while writing clues, look for opportunities to imply a fact by filling every square except one in a row or column. With enough variety in the clues, you’re bound to have a bunch of these without having to plan for them.

- A mutually exclusive list (“Donatello, the scientist, and the man at the ancient temple were grateful…”) is a good way to introduce mulitple terms and dimensions. It also states multiple negative associations (Donatello is neither the scientist nor the man at the temple) in a backhanded way.

- Gendered pronouns are a traditional way to mention negative facts about characters with names: “The zoo keeper was accustomed to stealth, and he managed to…” implies that neither Hannah nor Jaquelin are the zoo keeper. Be careful to avoid names that would be considered unisex or an opposite gender in different cultures. I used Gender Checker as a sanity check, though I have no way of knowing how well their data meets the expectations of the global IF community. I also included a gender-neutral character with a corresponding pronoun, which I hope reads as an IF reference. Gender representation and diversity is an important topic in IF, both as subject matter of interest to the community and as an inherent challenge in writing player and non-player characters. For this puzzle, I thought it better to embrace the challenge than to avoid it, and exploit pronoun-based clues.

- Many advanced logic puzzles use a dimension with ordered terms, such as the zebra puzzle’s houses arranged left to right, or an order of events. Sometimes this is treated as a “hidden” dimension, possibly even one that cannot be solved completely. Ordered terms make the logic more challenging, and introduce more opportunities for interest in the writing. I decided not to do this in the final version of this puzzle, but it wasn’t for lack of trying.

- It is traditional to pose a question more specific than “describe everything.” This is usually an opportunity to introduce an unfamiliar term with more backhanded language, one that will be associated with other terms in the negative space of the puzzle logic. Answering this question is a final glory for the player, since the unfamiliar term is not mentioned in any of the clues. The question about the whistle was originally a clue statement, and I rewrote it as a question in the final draft. I didn’t bother to check if the specific question about the whistle could be answered from a subset of the clues, but I assumed that players would try for a complete solve regardless.

Here is the intended solution.

The letter

The puzzle elements in the letter were straightforward, since I already knew they would appear on the page in the mysterious blue color, all caps and in Inconsolata to match the numbers on the certificate, and sideways to further reinforce that the puzzle world is not part of the letter world.

For the letter itself, I wrote a paragraph about the author’s winning game, and also provided some background information about the book they selected. I like these books so I have a lot to say about them, and I had to edit myself down to leave room on the page for the puzzle. I also liked the games! I was concerned that the more non-puzzle material I included with the prize, the less “efficient” the puzzle package would seem, and the more likely non-puzzle material would be misconstrued as puzzle material. But I figured my visual cues were thorough enough, and the letter contents would be appreciated regardless.

Another assembly snafu: one packing box was sealed with the packing slip in place of the letter. Good thing I had extra packing boxes.

How it went

All six recipients were appreciative of the prize package and recognized that there was a puzzle involved. Though none of them made it through the intended path to the end, they all gave it a go. I’m merely a hobbyist game designer (and a neophyte at that), but one thing I know to be true is that playing someone’s game is the highest compliment, even if you don’t like it. My thanks to them all for trying it out!

I shipped the prizes to recipients outside the United States on December 6th, and the prizes inside the United States on December 9th, to improve the likelihood that all players would receive them at about the same time. According to USPS Priority Mail shipment tracking, three of them arrived on December 12th, and the rest trickled in throughout the next couple of weeks.

Elize (Unform) was the first to make contact. She found me on Twitter pretty quickly:

Hey @dan_sanderson! Thanks for the incredibly generous book - and the swell certificate. Say I noticed a bunch of blue letters #anyrules?

— Elize Morgan (@elizemorgan) December 13, 2014@elizemorgan You're welcome! ...Blue letters? Probably a printer malfunction. Sorry about that. 😇

— Dan Sanderson (@dan_sanderson) December 13, 2014@dan_sanderson Printers, right? They're the worst.

— Elize Morgan (@elizemorgan) December 13, 2014Richard of Fear of Twine (Zest) did not find me, but used Twitter to tell his collaborators about the prize:

Well would you look at what came in the mail! Cc @lectronice @paperblurt pic.twitter.com/J8vrRrlgCD

— Richard Goodness (@richardgoodness) December 13, 2014@richardgoodness @lectronice yeah! Looks like a harvard degree!

— PaperBlurt (@PaperBlurt) December 13, 2014@richardgoodness @PaperBlurt @lectronice ooooooooooooh

— Gnome (@gnomeslair) December 13, 2014@richardgoodness @PaperBlurt I've just woke up and this is absolutely surreal. Kind of stuff you'd get in a bizarre school dream.

— lectronice (@lectronice) December 13, 2014@lectronice @PaperBlurt dude. There's a puzzle hidden in the frame. I will scan it later.

— Richard Goodness (@richardgoodness) December 13, 2014@richardgoodness @lectronice scan like you've never scaned before!

— PaperBlurt (@PaperBlurt) December 13, 2014Simon (Enigma, Tower) also found my Twitter account and sent thanks, though no mention of the puzzle.

@dan_sanderson Hello Dan, your parcel arrived today. Thank you for the book and the nice certificate. Greetings from Germany.

— Simon Deimel (@siddi1976) December 30, 2014(I’m eliding from this article the names of the players that did not contact me in a public forum to protect the privacy of their prize choices.)

With all packages delivered and enough holiday time for players to make progress on their own, but no visible evidence of progress or further contacts, I waited until the new year to send out a hint email. I purposefully included all players’ addresses in the recipients field so players could discuss the puzzle on the thread.

I got immediate replies that confirmed that two players managed to decode the cryptogram without ever finding the key, and were confused by the other puzzle elements and the incomplete logic puzzle. I should have suspected that some would attempt this path, even if it was challenging (and maybe it wasn’t), given how well the key was hidden. Cryptograms are often solvable and meant to be solved without keys. I started to worry that the incomplete logic puzzle might actually look like a complete logic puzzle that’s impossible to solve. I don’t mind leaving players in a stuck state, but I do mind misleading them to try and solve the wrong puzzle.

Two more players confirmed they found the overlay and recognized it as an overlay, one due to the glass breaking during shipment. At this point they had not solved the symbol-to-number puzzle. It’s possible they believed the overlay was for the certificate, as my 9-year-old had predicted.

One player recognized the symbols as being from the Wingdings font and attempted to decypher the symbols as a font-based substitution cypher. This was a neat idea, and in retrospect, it would have been fun to spell out “red herring” with the symbols or something.

Several players responded to my emails with follow-up questions. Notably, they were all replying directly to me, and not to the group, probably to avoid spoiling it for others. One player thought to ask whether all players received different puzzles, and I confirmed, hoping this would hint at the joint-effort finale. But it was unclear how interested the players were in taking it to the end, and it seemed nobody was going to start a group discussion.

A few days later, I sent another more generous hint email so anyone still interested could play with it a bit more over the weekend. I used a ROT-13 encoder/decoder to send a batch of five hints that the players could decode one at a time, as needed. A week later, I sent a second batch of hints, effectively a walkthrough up to the final logic puzzle. With no group discussion occurring, at least not where I could see it, I gave everyone until the end of January, then sent the complete decoded logic puzzle (without its solution) to the group, along with a link to this article.

Conclusions

I continue to be enamoured with the idea of making a game to be played by a very small number of people, and I’m sure I’ll try it again. But sending a game to strangers that aren’t expecting to play is inherently tricky. Large puzzle quests like Cards Against Humanity’s Ten Days or Whatever of Kwanzaa rely on having a large number of potential participants to get a small number of dedicated players sharing their results with everyone else. In particular, a large player base can overcome (and possibly necessitate) a high level of difficulty or obfuscation. A small group requires different accommodations.

Hiding something in the frame was one of my earliest ideas, and I probably should have discarded it. A hidden artifact is not really a puzzle, at least without a sizable hint. The first step needs to be the most obvious to build player momentum, and this ended up being the least obvious. It’s possible that the “use the book” leap was also too tricky, though not enough players made it that far for me to tell. Placing the overlay directly in the book (inside the cover, not on the intended page) would have made everything more accessible, and may have maintained the “hidden puzzle” spirit of the game.

Now that I know some players might tackle a cryptogram head-on, in retrospect, I would have used a different method to obfuscate the message. I considered having missing letters instead of a cypher, with the blanks filled in by letters revealed on the page, but at the time I was overly concerned that this would constrict how the messages were written. I’m still not convinced a tracing paper overlay can accurately select individual letters off of the typical typeset page of a book. A code that identifies word or letter locations on pages numerically might have been just as interesting and more robust.

The lack of inter-player communication was not surprising, though it’s still interesting how it didn’t pick up after I started an email thread. Keeping the game offline made each puzzle package seem self-contained. Even if by the end it seemed like one puzzle needed to interlock with something outside of the package, it was so difficult to locate other players that the difficulty itself might have been an anti-hint. While it would have been fun if this part were successful, the layout didn’t accommodate how failure at this step could be un-fun, even with my email hints as a backup plan.

I have other ideas for improving these aspects of the design, but I’ll keep them quiet for now. I might use them later. =)

Thanks again to the prize recipients for playing! And congratulations to everyone who entered IFComp 2014. Go play their games, and if you’re so inclined, go get Twine or Inform 7 and try making a text game of your own. IFComp 2015 registration opens July 1st. Who knows, you might win a prize.